Nazia Arfi n MSc, RGN

- Diabetes Specialist Nurse

- Manchester Diabetes Centre

- Manchester, UK

If these responsibilities are met fully arteria vesicalis inferior buy cheap dipyridamole 100mg line, a flight surgeon can make a real contribution to the understanding of the causes of aircraft accidents arterial blood gas values purchase dipyridamole 100 mg amex, to continued improvements in protective clothing and equipment blood pressure medication starts with t cheap dipyridamole 100mg on line, and to an ever-improving safety record in naval aviation heart attack 86 years old effective dipyridamole 100 mg. In summary, the postmortem examination of an accident victim can provide important information on the causes of an accident, information not obtainable through any other source. However, for the autopsy examination to be most effective, there are three issues which must be faced. As stated previously, there are many instrumentalities of government to be dealt with in handling a fatality, particularly when the accident does not occur on federal property. These arrangements can be expedited by establishing liaison with local authorities and physicians prior to any accident. Provision should also be made for consultations with the legal officer representing the naval district or the supporting naval air station. The flight surgeon should participate to the fullest extent possible in the aviation autopsy examination. The pathologist may be an outstanding examiner with a wealth of experience in performing routine postmortem examinations, but is rare indeed when his experience includes expertise in handling remains from aircraft accidents. The flight surgeon makes an important contribution, therefore, by defining the questions that should be asked in the examination. The pathologist relies on the flight surgeon and his understanding of aviation operations, current aircraft, protective equipment, and specific aircraft systems to ensure that the right questions are addressed. An aviation physiologist working with the team can often further characterize the relationship of injuries. Chapter 23, Aircraft Accident Investigations, elaborates on the various duties of the flight surgeon as a member of this board. A few words are in order here, however, concerning the disposition of issues which may arise during the autopsy examination. There is a requirement that the Aircraft Mishap Board and the flight surgeon, working together, address any problem that arises in the medical investigation which is of significant import. The Aircraft Accident Report and the Flight Surgeons Report must be complementary. It is interpreted to mean that the same issues must be treated, and evidence must be presented that the two sides have communicated on medical issues of significance and that each has developed its position addressing that problem. He does bear the responsibility for seeing that medical findings that may have relevance in determining accident causation or in improving issues of aviation safety are given full weight in the conclusions of the Aircraft Mishap Board. Reconstruction of the mishap scenario by injury patterns requires the separation of observed injuries into discrete categories. Major categories in aircraft mishaps include deceleration, direct impact, flailing, intrusion, thermal and environmental. American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons symposium on the spine, Cleveland, November 1967. Disaster planning for air crashes: A retrospective analysis of Delta Airlines Flight 191. Lieutenant Bertram Groesbeck becomes the first naval medical officer to complete flight training and be designated a naval aviator. Upon completion of flight training, Groesbeck reports to the Army School for Flight Surgeons, graduating on 27 April 1923. Chiefs of the Bureau of Aeronautics and the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery agree upon the qualifications for designation as a naval flight surgeon. Army School of Aviation Medicine and three months of satisfactory service with a naval aviation unit prior to designation. The requirement that a medical officer so qualified also make flights in aircraft was limited to emergencies and to the desire of the officer. Research into the physiological effects of high acceleration and deceleration, as encountered in dive-bombing and other violent maneuvers, is initiated by the 8 Nov 1921 29 Apr 1922 1922 1923 14 Nov 1924 18 Jan 1927 28 July 1932 A-l U. This pioneer research pointed to the need for anti-G or antiblackout equipment and was conducted at the Harvard University School of Public Health by Lieutenant Commander John R. This belt was to be used by pilots, in dive-bombing and other violent maneuvers, in order to protect against blackout. A medical officer is detailed to the Bureau of Aeronautics for the purpose of establishing an aviation medical research unit. The first instruction in aviation medicine at the Naval Air Station, Pensacola, Florida, begins with the reporting of nine reserve medical officers to the Medical Department. The first class was graduated on 20 January 1940 as Aviation Medical Examiners after a 60-day course of instruction.

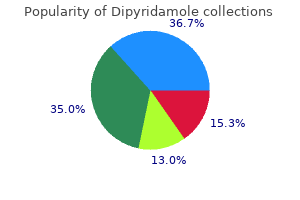

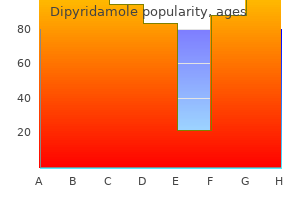

Clin Chem 17:851-866 blood pressure chart good and bad discount 25 mg dipyridamole amex, 1971 I hesitate to indicate textbooks in police science and investigation blood pressure medication morning or evening discount dipyridamole 100 mg on line. However class 4 arrhythmia drugs buy dipyridamole 100mg without a prescription, I would suggest as a most provocative article the following which deals with "eyeball" witnesses: reading this may change your mind relative to "investigational" information arteria hypogastrica order dipyridamole 100 mg overnight delivery. The goal of the collaborative project is to improve the quality of pain management in health care organizations. This monograph is designed for informational purposes only and is not intended as a substitute for medical or professional advice. Readers are urged to consult a qualified health care professional before making decisions on any specific matter, particularly if it involves clinical practice. The inclusion of any reference in this monograph should not be construed as an endorsement of any of the treatments, programs or other information discussed therein. Factors that prompted such attention include the high prevalence of pain, continuing evidence that pain is undertreated, and a growing awareness of the adverse consequences of inadequately managed pain. About 9 in 10 Americans regularly suffer from pain,1 and pain is the most common reason individuals seek health care. Sufficient knowledge and resources exist to manage pain in an estimated 90% of individuals with acute or cancer pain. Data from a 1999 survey suggest that only 1 in 4 individuals with pain receive appropriate therapy. Individuals with poorly controlled pain may experience anxiety, fear, anger, or depression. The authors of this guideline acknowledged the prior efforts of multiple health care disciplines. Due to the breadth and complexity of the subject matter, a comprehensive discussion of all aspects of pain assessment and management is beyond the scope of this monograph. The scope and potential limitations of this monograph are as follows: s the neurological and psychological mechanisms that underlie pain are complex, and knowledge of mechanisms is limited. The discussion of pathophysiology in this monograph emphasizes practical knowledge that will facilitate diagnosis and/or the selection of appropriate interventions. This monograph provides an overview of pain assessment, but primarily focuses on the initial assessment. This monograph reviews pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments for pain, with greater emphasis on the former. Specific information about the treatment of certain conditions is limited to some common and treatable types of pain. The discussion of pharmacologic treatments emphasizes: 1) the major classes of drugs used for pain management; 2) examples and salient features of these drugs; and 3) some means of ensuring the safe, strategic, and effective use of these agents. Due to the large volume of associated literature, a review of the mechanisms, assessment, and management of pain associated with some conditions. In 1968, McCaffery defined pain as "whatever the experiencing person says it is, existing whenever s/he says it does". It also stresses that the patient, not clinician, is the authority on the pain and that his or her self-report is the most reliable indicator of pain. But classic descriptions of pain typically include four processes:20-23 s Transduction: the conversion of the energy from a noxious thermal, mechanical, or chemical stimulus into electrical energy (nerve impulses) by sensory receptors called nociceptors s Transmission: the transmission of these neural signals from the site of transduction (periphery) to the spinal cord and brain s Perception: the appreciation of signals arriving in higher structures as pain s Modulation: descending inhibitory and facilitory input from the brain that influences (modulates) nociceptive transmission at the level of the spinal cord. The goal is to provide practical information that will facilitate pain assessment and management. A questionand-answer format is used to provide information about the following: s the definition of pain s the process by which noxious stimuli generate neural signals and the transmission of these signals to higher centers (nociception) s the role of inflammatory mediators, neurotransmitters, and neuropeptides in these processes. Nociceptor activation and sensitization Nociceptors are sensory receptors that are preferentially sensitive to tissue trauma or a stimulus that would damage tissue if prolonged. Signals from these nociceptors travel primarily along two fiber types: slowly conducting unmyelinated C-fibers and small, myelinated, and more rapidly conducting Adelta fibersc (Figure 2). Injury to tissue causes cells to break down and release various tissue byproducts and mediators of inflammation. The functioning of nociceptors depends upon the electrophysiological properties of the tissues, co-factors, and cytokines. Peripheral (nociceptor) sensitization amplifies signal transmission and thereby contributes to central sensitization and clinical pain states (see I. Peripheral neuropathic pain Not all pain that originates in the periphery is nociceptive pain.

Left) A synovial sheath surrounds a tendon over a greater distance and facilitates its frictionless movement arrhythmia can occur when cheap dipyridamole 25mg otc. Reflection of the synovial membrane creates the supporting mesotendon arrhythmia pac order dipyridamole 25 mg otc, through which vessels and nerves gain access to the tendon blood pressure chart log excel dipyridamole 100 mg for sale. Right) A bursa lies interposed between a tendon or ligament and a bony prominence arrhythmia alcohol discount dipyridamole 25 mg amex. The double fold of membrane formed where the edges of the synovial sheath meet is the mesotendon. Low-grade trauma (for instance, as associated with rigorous schooling of young horses) may result in a mild, painless tenosynovitis of the digital flexor tendon sheath (windpuffs) or the deep digital flexor tendon sheath proximal to the hock (thoroughpin). Muscles Acting on the Shoulder Girdle the scapula and shoulder can make complex movements in humans, but in domestic animals the chief movement of the proximal part of the thoracic limb is a pendulous swing forward and backward. These muscles are also critical in allowing the weight of the thorax to be supported between the two thoracic limbs. The portion originating cranial to the scapula helps swing the scapula forward; the one attaching behind draws it back. The cervical portion, on contraction, tends to rotate the distal part of the scapula backward, while the thoracic portion rotates it forward. It takes origin from the transverse processes of the more cranial cervical vertebrae and inserts on the distal part of the spine of the scapula (clavicular tendon in the horse). Muscles Acting on the Shoulder Joint the shoulder, being a ball-and-socket joint, can make all types of movement. The origin is from the occipital bone of the skull and transverse processes of the cervical vertebrae. It inserts on the lateral side of the proximal part of the humerus proximal to the deltoid tuberosity. It inserts on the greater tubercle (both greater and lesser in the horse) of the humerus. This is one of the muscles that atrophies (shrinks) in sweeny in horses, a condition that results from damage to its motor innervation, the suprascapular nerve. The attachment of limbs to the trunk is achieved through a synsarcosis, rather than by a bony joint. Also, it pulls the thoracic limb caudad or, if the limb is fixed, advances the trunk. They originate from the sternum and insert mainly on the proximal part of the humerus. These pectoral muscles are strong adductors of the forelimb, and the deep pectoral muscle also advances the trunk when the limb is fixed on the ground (weight bearing). This muscle is part of the support of the trunk and contributes to stabilization of the shoulder joint. The location of the muscle belly suggests a shoulder flexor, but its attachments make this muscle an extensor of that joint. It originates from the subscapular fossa on the medial side of the scapula below the attachments of the m. It inserts on the lesser tuberosity of the humerus and provides some adduction to the shoulder joint. It also originates on the humerus, inserts on the olecranon process, and extends the elbow. The flattened muscle belly lies on the caudomedial aspect of the arm and inserts via a second aponeurosis on the olecranon and antebrachial fascia. Muscles Acting on the Elbow Since the elbow is a hinge joint, the muscles acting on it are either flexors or extensors. In quadrupeds, the extensors are stronger than the flexors because they support the weight of the body by maintaining the limbs in extension. The long head originates from the caudal border of the scapula, and the medial and lateral heads originate from the respective sides of the humeral diaphysis.

There has been concern for many years that subclinical cardiovascular system damage might occur from high G exposure blood pressure chart for 14 year old dipyridamole 100mg cheap, causing long-term adverse health effects arrhythmia originating in the upper chambers of the heart buy dipyridamole 25 mg online. In fact blood pressure medication drug classes buy cheap dipyridamole 100 mg on-line, endocardial hemorrhages have been reported in pigs exposed to high G pulse pressure 28 cheap 25 mg dipyridamole visa, but there is no evidence that cardiac 2-4 Acceleration and Vibration damage occurs in humans who are exposed acutely or chronically to G within tolerance limits (Leverett & Whinnery, 1985, p. Potency of various arterial pressure control mechanisms at different time intervals after the onset of a disturbance to the arterial pressure. If blood flow to these tissues is interrupted, the tissue reserves of oxygen last approximately 5 seconds. If blood flow is restored after a brief period of malfunction, the tissue resumes functioning with no residual damage. There is, however, a profound and critical difference between the response of the eye and the response of the brain to blood flow loss from +Gz. First, blood flow to the eye ceases before blood flow to the brain does, because of the internal pressure of the eye (approximately 16 mm Hg average). Aviators frequently use grayout or tunneling of vision as a way to titrate the G load to avoid more serious consequences, but this technique becomes less reliable as the G onset rate increases. To understand this phenomenon, it is necessary to examine the interactions between the 5-second lag from stoppage of blood flow to eye or brain until the development of eye or brain symptoms, and the onset rate of G. Figure 2-2 illustrates this warning time change at a slow and a fast onset rate of G. The dotted line shows a rapid onset of G to 8G in an aviator who loses blood flow to his eye at 6G and to his brain at 6. Figure 2-3 further illustrates the physiology of G-induced visual symptoms and loss of consciousness. Note especially the 5-second oxygen reserve during which no eye or brain symptoms occur. This reserve explains why an aviator can bend an airplane with momentary excessive G, have no ill effects, and as a result, develop an inflated perception of his G tolerance. The dip in the curve in Figure 2-3 illustrates the problem caused by the lag in physiological compensatory 2-6 Acceleration and Vibration mechanisms, especially with high onset rates of G. It also illustrates such as the F/A-18 that are capable of high for the visual symptoms to provide warning Figure 2-3. This can be easily demonstrated by digital pressure on the eye to stop the blood flow (Whinnery, 1979). After about 5 seconds of pressure, vision is progressively lost from peripheral vision to central vision. Cerebral failure and recovery is much less graceful and predictable (Houghton, McBride, & Hannah, 1985). When consciousness is regained, it is usually accompanied by brief seizure-like activity and a period of confusion, which lasts about 12 seconds. An additional period of up to 2 minutes is required before cognitive and pyschomotor performance ability recovers to normal. Total loss of the ability to control a high performance, unstable aircraft for half a minute is obviously a condition to be avoided. As the +Gz increases, the pressure gradient in the lung increases, resulting in reduced perfusion of the upper part of the lung and increased perfusion in the lower part of the lung. This results in an increased physiological dead 2-8 Acceleration and Vibration space in the upper portion and a physiological shunt in the lower portion of the lung, both of which result in a reduced PaO2. This reduced PaO2 is added to the insult of reduced blood flow to the head and would be expected to contribute to decrements in performance capability. Navy uses 100 percent oxygen in most tactical jet aircraft breathing systems to simplify the breathing system, to provide an underwater breathing capacity, and to maximize night vision. Aero-atelectasis, especially in the compressed alveoli of the dependent portion of the lung, occurs more readily when 100 percent O2 is used than when an inert gas dilutes the breathing gas, due to the more rapid absorption of O2 from poorly aerated alveoli. The aero-atelectasis sometimes causes mild transient chest pain and coughing after high +Gz maneuvering, but the symptoms are generally not thought to be severe enough to offset the advantages of the 100 percent O2 systems. At 6 +G z, a 160 pound aviator is pressed into his seat with an equivalent of 960 lbs.

Buy dipyridamole 100mg low price. Reasoning Speed Quiz 15 Live | Blood Relation with Shyam Sir for IBPS RRB RBI NIACL.

References

- Finfer S, Bellomo R, Boyce N, et al. A comparison of albumin and saline for fluid resuscitation in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(22):2247-2256.

- Spampanato C, De Leonibus E, Dama P, et al. Efficacy of a combined intracerebral and systemic gene delivery approach for the treatment of a severe lysosomal storage disorder. Mol Ther 2011;19:860.

- Allain H, Bentue-Ferrer D, Polard E, et al. Postural instability and consequent falls and hip fractures associated with use of hypnotics in the elderly: a comparative review. Drugs Aging 2005;22(9): 749-65.

- Riddell SR, Greenberg PD. Principles for adoptive T cell therapy of human viral diseases. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:545-586.

- Hochman JS: Cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction: Expanding the paradigm, Circulation 107:2998, 2003.

- Kumer SC, Vrana KE. Intricate regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase activity and gene expression. J Neurochem. 1996;67(2):443-462.